Remembering Black History Month at Amherst

Staff Writer Sarria Joe ’27 investigates what Amherst has done for Black History Month historically and explores the efforts of student organizations to create Black History Month events.

Many students have expressed that the college’s efforts to acknowledge and celebrate Black History Month on campus this year were insufficient and inconspicuous.

“There hasn’t been enough support, I would say, coming from the administration,” said Association of Amherst Students Senator George Daniel Dixon ’27. “I think the whole campus, alongside the President, just doesn’t engage with Black History Month enough, and I don’t feel supported.”

Neither the President, the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, Student Engagement & Leadership, Student Affairs, or the Civil Rights & Title IX Office made the gesture of wishing the campus a “Happy Black History Month.”

“I feel like my high school did better because — even to this day [Feb. 28] — there was no formal announcement. And if I’m being honest, I kind of forgot about Black History Month because of how silent it has been,” Arianna Dempsey ’27 said.

This is not to say that the entire administration is apathetic in its efforts to acknowledge and commemorate Black History Month. Still, it prompts questions and concerns for many students, who say they have witnessed little to no programming from these core institutional departments.

“A lot more can be done. A lot more needs to be done to support Black students and make them feel good about their community. Silence is way worse than minimal effort because silence is nothing,” Dempsey said.

Most events explicitly organized to celebrate Blackness or Black History Month were organized by the Multicultural Resource Center, the Black Students’ Union (BSU), and the African and Caribbean Student Union.

These student responses made me wonder: what has Black History Month at Amherst looked like historically? And who has carried the burden of organizing events over time? I went into the archives and interviewed administrators and students to uncover the history and goals of Black History Month at Amherst.

Black History Month Through BSU’s Archives

The archival documents pertaining to the BSU, previously called the Afro-American Society, display the evolution of organizing and collaboration between black students at Amherst. From letters to fliers to meeting notes, we can witness what Amherst was like for Black students in the past, especially during Black History Month.

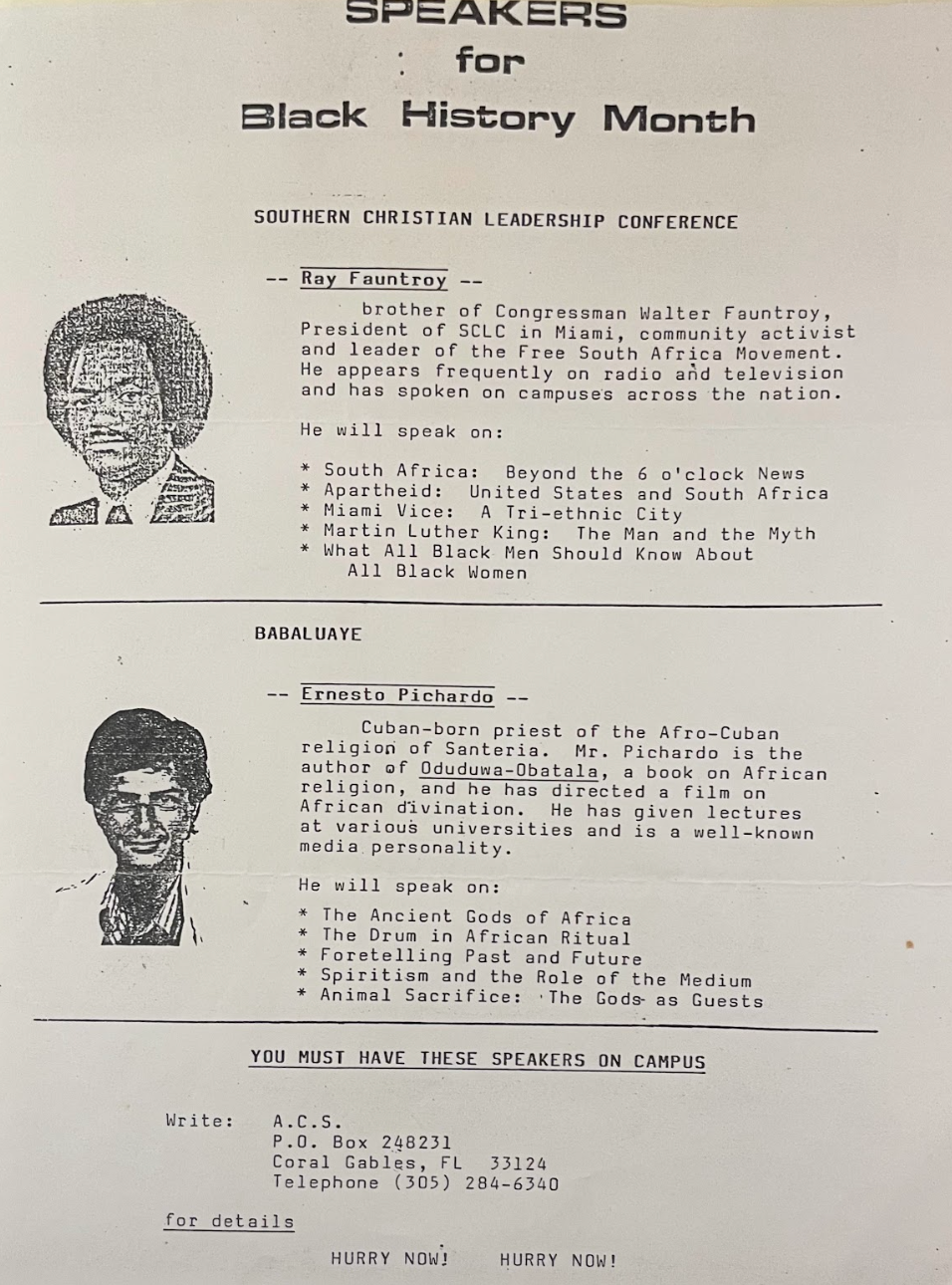

Around 1978, the BSU invited two prominent speakers for Black History Month. Ray Fauntroy was president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference at the time and “community activist and leader of the Free South Africa Movement,” according to a flier. He spoke on issues of South African apartheid, the martyrdom of Martin Luther King Jr., and even “What All Black Men Should Know About Black Women.” The BSU was committed to ensuring that a range of religious perspectives were honored during this time. The second speaker was Ernesto Pichardo, an Afro-Cuban Santeria priest and author of “Oduduwa Obatala,” which discussed Nigerian Yoruba religion. Some titles from Pichardo’s discussion were “The Ancient Gods of Africa,” “Spiritism and the Role of the Medium,” and “Animal Sacrifice: The Gods as Guests.”

In February 1980, the BSU organized a Black History Month event that included a lecture by Alfred “Skip” Robinson, president and founder of the United League, a social movement that worked to fight police brutality and the Ku Klux Klan in Northern Mississippi. Other programming included a Black history photo exhibition — although the archives did not provide further details about the content of the exhibition. Other speakers included the Chairman of the Democratic National Committee, a feminist writer from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and a corporate attorney.

The BSU also organized concerts to celebrate Black artists, such as the 1982 Black Classical Music Concert featuring Marion Brown, a renowned American saxophonist and member of the avant-garde jazz scene in New York in the 1960s.

The administrative materials included a note: “The concert is co-sponsored by the Amherst College Third Wor[l]d Cultural Committee.” In later years, this cross-committee and institutional collaboration played a prominent role in planning and executing Black History Month events at Amherst.

The BSU also created opportunities off-campus, including a trip to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, a prominent cultural institution committed to preserving and exhibiting works centered on the experiences of African Americans and the African diaspora.

On Feb. 21, 1987, a Black history tournament was held in Charles Drew, which was based on a black history board game called “RISE-N-FLY.” Despite the racial targeting at this time and rampant violence against Black communities due to the war on drugs, it’s worthy of note that the BSU also prioritized celebrating black joy and rest.

In collaboration with La Causa and the Women’s Center, the BSU worked on programming to highlight Black voices and experiences throughout the year as well. In the 1980s, they drafted a proposal for “Development Dialogue,” a student and faculty forum “seeking to educate the Amherst College community on conditions of development in the Third World through the use of films, speakers, and discussions.”

Decades later, affinity groups and resource centers still bear much of the weight of organizing such programming. Today, programming aimed at fostering community among Black students is nowhere near as robust.

Centering Black Women

In their 1976 Constitution, the Afro-American Society stated, “With the admittance of black Women into this college, it is necessary to look for their welfare not only as black students, but as black women ... therefore, this cell will deal specifically with issues of interest to Black women.”

Among the recurring events created specifically for Black women was Black Women’s Weekend. According to a tentative schedule in the BSU files, the title or theme of this weekend was “Black Women in America: Careers and Choices Today.” The weekend included a lecture or discussion about “black women’s role in American society past, present, and future” and “what she should be about today through careers” and a career workshop. There was also a “Soul’s Release,” which “is sort of like a talent show. People are invited from the immediate area to contribute any performing talent they may have ... This affair is ‘releasing one’s soul’ and is usually very informal.”

The group in the Afro-American Society on Black women eventually evolved into a position represented by a Black woman whose primary goals were to advocate for the interests and policies relevant to Black women and “coordinate black women’s [weekend].”

The Martin Luther King Committee

The Martin Luther King Committee (MLKC) was developed in the early ’90s in collaboration with several other departments on campus. Then Affirmative Action Officer and Ombudsperson Hermenia Gardner delineated a three-part concept statement: interfaith worship service, lecturer, and cultural event.

It appears that this was the first time that the administration made a concerted effort to commemorate Black History Month. The committee was sponsored by the President’s Office, the Affirmative Action Office, and the Black Steering Committee, among others.

The committee invited speakers such as the God Squad of ABC’s Good Morning America, Reverend and civil rights activist Jesse Jackson, Reverend Bernice King (daughter of Dr. King), and Reverend Nathan Baxter Dean.

“We invited some famous folks who come and talk, and then they would tell this story, and we would have a light meal and song, but we did it to raise money for the local survival center,” Senior Associate Dean of Students Charri Boykin-East said.

One of the dinner discussions was the “The Darfur Project,” in which students, professors, faculty, and others in the Amherst community gathered to savor a Sudanese meal while learning from Smith College English Professor and Darfur Analyst Eric Reeves about what efforts can be made to help people in the Darfur genocide.

“One of the cultural programs included the Harlem Gospel Choir performing several times at the college … culminating our month-long campus programs. Each performance was well attended by students, faculty, staff, and community members,” Boykin-East said.

The college also invited Jean Thompson, a Freedom Rider, to discuss her experiences in 2009.

In February 2011, Reverend Samuel “Billy” Kyles, a civil rights activist and last witness to King’s assassination, spoke on his life and works.

Some of the last recorded events organized by MLKC were from 2013.

“I am not aware that the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Committee currently exists. I would like to see this Committee be revived. It was a Committee that included faculty, staff, students, and community members. All working in partnership to offer education and culture in an effort to enhance conversations on campus. It was a group that worked in collaboration to build community,” said Boykin-East.

This article is the first in a series investigating what Black History Month looks like at Amherst. A follow-up article will explore what is being done for Black History Month now, what students and administrators hope to see, and evaluate how the past can inform our future.

Comments ()